In mid 2019 I took on a 50%-time role as “Advancement and Learning Facilitator” in Broad’s Data Sciences Platform. One of my big projects in this role was to rethink our software engineering ladder. This is a writeup of that process, and the result.

The problem

The group had inherited a venerable document called the “Software Engineer Job Family Matrix”, dated May 2011. It was a two-page table outlining job responsibilities and requirements at each level, and was written at a time when software engineers were typically hired in ones and twos, directly by PIs for their academic labs.

The levels were, in order:

- Associate Software Engineer

- Software Engineer

- Senior Software Engineer

- Principal Software Engineer

- Senior Principal Software Engineer

- Manager, Software Engineering

The job matrix was widely considered to be a relic of its time and unsuitable for an independent software engineering group of 50-100 people. This caused a few problems:

- Engineering Managers used their own heuristics for judging when an employee was ready for promotion: a common one was “how much code can the engineer handle responsibly on their own?”, ranging from “a function” for ASEs to “a moderately sized service” for PSEs.

- However, there was a wide degree of variance between EMs on other qualities necessary for promotion, especially around what was termed “soft skills”.

- New leadership joining the organization felt that titles were inflated by around one full level, in part because there was little flexibility in comp inside salary bands: engineers got bumped up to the next band in order to attract and keep good talent.

As a result, engineers seeking promotion would sometimes be told “we don’t think you’re ready yet”, with little provided in the way of actionable feedback. In a couple of cases, engineers were told by their managers they were a shoo-in for promotion, only to have their promo vetoed at the next EMs meeting. This understandably caused some consternation.

Questions arise

In response to this, engineering leadership met to ask and answer some questions:

- What are the actual criteria that EMs are using?

- How do we make sure that promotion criteria are being applied consistently between EMs?

- Can we use our engineering ladder as a way to move our desired skillset away from the “brilliant jerk” archetype, towards prioritizing maturity and collaboration?

The vision

We decided a good career ladder should have the following attributes:

- A set of rubrics with very clear, check-off-able criteria for each level;

- Finer granularity on those criteria, leading to more consistency between EMs;

- Any disagreement between EM and employee should be focused on “are these sufficient examples of me fulfilling this criteria”, not “what are the criteria”;

- Criteria are specific enough that EMs + reports can actively build opportunities to demonstrate them.

The process

Build a deck of “skill cards”

With help from an interested EM and an enthusiastic SE seeking promotion feedback, I sought out engineering ladders from other companies (including Medium’s snowflake model and Rent the Runway’s great spreadsheet) and decomposed them into “skill cards”, each of which had a single skill or quality that an engineer might display.

Both the original job matrix document we used, and many of the engineering ladders we found online, were very skewed towards listing technical skills. We took extra care to find and create skill cards around collaboration and emotional maturity. We also added some antipattern cards - common pitfalls for engineers at a given skill level.

Order the skills relative to each other

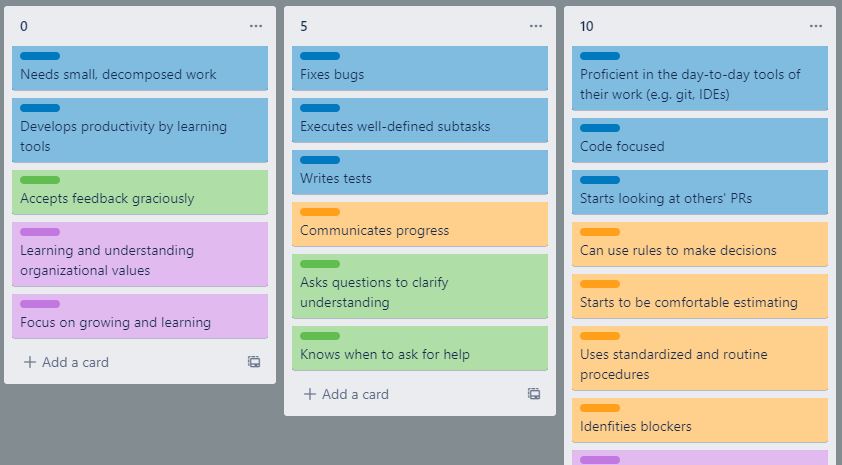

Next, we created a Trello board which contained:

- All the “skill cards”; and

- A large number of empty Trello columns, labelled 10, 20, 30, …

The EMs were then assembled and, as a group, played a game of The Price Is Right: which numbered column should each skill card go in? Higher or lower, relative to the skill cards that were already placed?

The columns were labelled with numbers, not levels: this was to prevent debates about whether a skill was “intermediate” or “senior”. The object was solely to order skills relative to each other; the group could choose to add additional columns, including between existing columns, as they felt necessary.

By the end of this step we had a Trello board with skill cards sorted into numbered columns, like this:

We ended up with 16 columns and 178 cards.

Define the level boundaries

From here the task was simple: decide where the level boundaries should be. By focusing on ordering the skill cards beforehand, we swapped the question “is X a Senior trait?” for the easier “how experienced do we want a Senior to be?”

With so many columns, this naturally meant that each level spanned many columns - which felt like a good indication of progress across a band.

Of course, it’s not realistic to expect every engineer to check off each skill in order, so the group also had to agree on what “ready for promotion” meant. We settled on the following:

You should read the columns as an attempt at describing a set of qualities an engineer might expect to acquire around the same stage in their career – though each engineer will of course grow and develop differently. If you were to shade the cards an engineer has “achieved”, we wouldn’t expect the shaded/unshaded boundary to span more than two or three columns; if this is not the case, some targeted coaching is probably a good idea.

Columns are labelled with the level they correspond to. We consider an engineer ready for promotion relative to the “boundary line” between two level columns. We expect to promote engineers when they have most (~75%) of the attributes in the column immediately left of the line, and some (~50%) of the attributes in the column right of the line.

What of the uppermost levels?

The group decided to punt on everything past the Principal boundary, for a few reasons:

- The skill cards started to get thin past there, pointing to a lack of experience among the EM team in evaluating very-senior candidates;

- The biggest need was providing clarity to engineers looking for promotions to Senior or Principal, which we’d filled;

- Promotions to Senior Principal were extremely rare = with only 5 or so SPs in the entire organization.

We rationalized this by saying that Principals have finished the mandatory-training part of their track and should now be focused on carving their own niche.

Communicate to engineers

Employees are naturally wary of changes to how they’re evaluated at work. EMs were asked to introduce and discuss the new framework with their engineers during 1-1s, rather than surprising everyone with a “big reveal” at an all-hands. We also wrote a document explaining the changes and answering the big questions, like “will anyone be re-levelled?”.

The result

You can see the final Trello board here.

At first engineers were a little overwhelmed, as the board is a lot to take in at once. But after that wore off, they appreciated the clarity.

Sadly, the new framework didn’t end up used as often as I’d hoped. Between turnover amongst the EMs and technical directorship, plus “no budget for promotion” issues, explicit use of this framework fell by the wayside. From what I hear, there has since been gradual attrition of longtimers with institutional memory, and a difficulty transferring that knowledge to new hires.

Epilogue

Since this project, the software industry has become a lot better at being clear around engineering ladders. Aggregator sites like progression.fyi host examples from many companies, including some implemented as Trello boards! I find this validating, though it does make it harder for me to claim I was being innovative 😉. Certainly were I to redo this project (and I’d enjoy doing so), there’d be many more resources to pull from - which can only be a good thing!